I’m anti-advice, as a rule.

I try not to give it and I rarely want to get it, especially not the unsolicited variety.

When I tell someone my problems and worries, I want to be heard and empathised with. I don’t want to be offered solutions, especially when they’re likely to be solutions that I’ve already thought of and dismissed for valid reasons.

Sometimes other grievers offer me advice and it’s mostly obvious stuff, like maybe you could try to meditate (no) or remember that how other people react to your loss is more about them than you (I know).

I get that it’s kindly meant and it’s great when people, in any challenging situation, have found some way through.

But although we’re all connected and share similar experiences, our understandings of the world and the things that make us feel better are so individual and often idiosyncratic that what works for someone else may be of no use at all to me — and vice versa.

For example, I’m proud that I’ve somehow managed to survive the last five awful months since my mum died but it doesn’t necessarily mean I have anything useful to offer someone who’s just embarked on month one.

Their life will likely be very different to mine. And although I sometimes find pieces of advice on the tip of my tongue and occasionally spit them out, deep down I know that we all have to make sense of our own trauma (or as Jamie Lee Curtis would say, “trow-ma”) and on our own schedule.

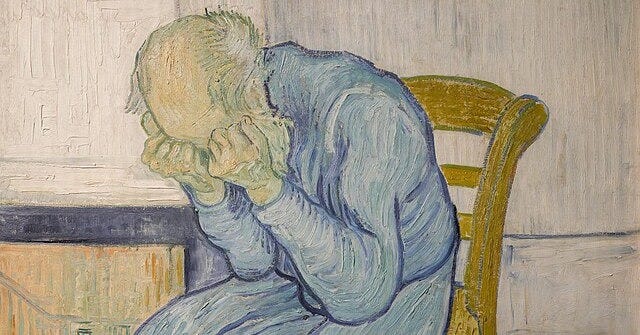

HAVING SAID THAT, I thought it might be helpful to me and anyone who is exactly like me (you poor thing) to reflect on how I’ve managed to get through a time that frequently felt unlivable, to record what I did so I can look back on it later if I ever need reminding and to remember that survival is possible even when it feels like it isn’t.

The most important thing for you (and by “you”, I mean me in the past and the future) to know is that you don’t have to do anything.

There’s a lot of advice (gahhhhhh) out there about coping, about breathing, about meditating, about going for long walks and having daily baths, about—BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH BLAH.

You don’t have to do any of that.

I feel very strongly about this and very angry when anyone tries to tell grievers how they should cope, because when even breathing feels barely possible, it’s cruel to ask someone to embark on a new routine, let alone utter one of my most-hated phrases, “self-care”. (I don’t care about self-care, so there!) (Look out for that post in 2025).

Whether you’re going through a bereavement or anticipating one or are battling through some other awful situation, it’s enough just to keep yourself alive. Really.

Probably you’ll need to eat something, to wash occasionally, to get a bit of sleep sometimes.

That’s it. That’s all.

Lower your expectations so they’re touching the floor. Doesn’t that feel better?

When I went to one of my first grief support groups, I was in a real state, tears pouring down my face and beating myself up for not having had a shower even though I’d planned to do it for the last eight hours and made a playlist to keep my brain occupied and everything.

The volunteer who was leading the group said something about how people “turn up not having had a shower for ages, having slept half the day because they were awake all night…” and I realised that this is a time when feeling awful and being unable to stick to a normal routine is inevitable, is normal, is a survival strategy, and that anything that keeps you alive is a good thing.

That can be a controversial idea, especially for people with experience of therapy, which often splits coping mechanisms into adaptive and maladaptive, i.e. good or bad.

But I remember once watching a video by a psychologist who said that anything that keeps you alive is a good thing.

Yes, of course it’s better for your health if you don’t start a heroin habit, but it’s preferable to suicide. Self-harm is not, objectively, the best thing for you, but it’s better than being dead.

A lot of people smoke, or drink, or binge eat, or overwork, or exercise too much and while I’m not saying those are brilliant decisions in the cold light of day, in the depths of grief, they might be keeping someone going, so I’ll never say they should stop.

We all have our vices, our ways to keep ourselves clinging to life, and despite what some ‘wellness’ experts will no doubt proclaim, I don’t think bereavement is the time to try to live a pure and abstemious existence, to be your most productive self or to attempt to honour your loved one by making them proud.

Just keep breathing. That’s enough. That’ll do.

The main thing really, above all else, is to remember that it’s normal to feel terrible. It will eventually get a tiny bit better but right now, you’re not doing anything wrong.

Just by keeping going, you’re doing everything right. Don’t give up. That’s all that matters. Don’t give up.

If you’re worried about your mental health, Samaritans are always there on 116 123 or try your local suicide helpline. If you’re concerned someone else might be suicidal, there’s guidance here.

I think the thing you offer someone in month one is that you’re still here in month five. You write this all so well- what a talent that is to be ‘in it’ and write this.

That is such a brilliant piece and probably one of the most helpful and sensible I have ever read concerning grief. As you say, just breathing is hard enough some days and things like personal hygiene can take a backseat sometimes, because in the scheme of things at that moment, who gives a shit? Just try to get through the day whatever it takes. Or doesn't. Repeat the next day. That's all.